The creation of the word ‘serendipity’

Posted on July 02, 2018

In this sixth instalment of our special blog series, we continue to follow art historian and provenance researcher, Silvia Davoli, on the trail of the lost treasures of Strawberry Hill House. This month, Silvia has been sleuthing for a striking Italian Duchess whose tragic fate cast a spell on the young Horace Walpole and inspired the creation of the word ‘serendipity’.

He doted on her for hours. The twenty-two-year-old Horace Walpole, a wide-eyed Grand Tourist, attending upon the peach-skinned Venetian beauty in the oil painting before him. Walpole was besotted with the portrait of Bianca Capello, which hung on the wall of the Casa Vitelli in Florence. It was only after some years, long after Walpole had returned from the Continent that his friend Horace Mann, the British envoy in Florence, would help him consummate the long-distance love affair.

Mann purchased Bianca in 1752 and in 1754 he presented it to his dearest friend Walpole. ‘It is an old acquaintance of yours, and once much admired by you’, Mann wrote to Walpole in 1753, ‘it is the portrait you so often went to see in Casa Vitelli of Bianca Capello… to which, as your proxy, I have made love to for a long while… It has hung in my bedchamber and reproached me indeed of infidelity, in depriving you of what I originally designed for you’.

When I discovered that Bianca’s portrait was among the lost treasures of Strawberry Hill House, I knew that I must do all I could to return Walpole’s long-lost lover to her home in Twickenham. Not only was I completely moved by Walpole’s ardour for the exquisite but doomed Duchess of Tuscany but I was thrilled to learn that Bianca provided the inspiration for the origin of the word ‘serendipity’. The chase is too tantalising to ignore.

I begin by tracing her arrival in England, which Walpole commemorated in a 1754 letter to his friend. ‘Her Serene Highness the Great Duchess Bianca Capello is arrived safe at a palace lately taken for her in Arlington Street’. Like an infatuated bridegroom, Walpole could barely contain his sheer delight in his bride’s homecoming and marvelled ‘the head is painted equal to Titian, and though done… after the clock had struck five and thirty, yet she retains a great share of beauty’.

Trawling through Walpole’s correspondence, I learn that Bianca was not fated to settle forever in Walpole’s London residence. As befitted her noble station, she was destined for the majestic round drawing room in the tower at Strawberry Hill House. In 1771, Walpole penned a letter to Mann, his honeyed words suggesting he was still in the throes of love for his duchess: ‘I am writing to you in the bow window of my delicious round tower with your Bianca Capello over against me, and the setting sun behind me, throwing its golden rays all around’.

As I plunge myself deeper into the archives of the Lewis Walpole Library I begin to wonder about this mysterious woman who bewitched the young Horace Walpole so completely. Bianca Capello (1548-1587), a member of one of the richest and oldest noble families in Venice, renowned for her ravishing beauty. Walpole did not stand a chance. At 15 years old, she fell in love with her first husband, Pietro Bona Venturi, a Florentine clerk. They escaped to Florence where they married. Before long Bianca was seduced by the heir apparent of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Francesco I de’Medici who showered his new mistress with money and jewels.

Their love affair was not without scandal. When Francesco became the Great Duke and his wife died, he is thought to have murdered Pietro so that Bianca was free to marry. Tragedy befell the Duke and newly crowned Duchess when they both died at the Villa Medici in Poggio a Caiano, victims of a suspected poisoning. It turns out I am on the hunt for a tragic muse.

I knew that Walpole adored this kind of melancholic tale and he possessed not less than three portraits of the ill-fated duchess at Strawberry Hill. What I need to determine if I am to have any hope of uncovering the missing work is who was responsible for his very favourite portrait?

There are many alleged depictions of Bianca, young and old, which somewhat complicates my search, but only two in which the identity of the sitter is completely certain. The portrait in Casa Vitelli, Walpole’s Bianca, had been attributed to Bronzino for a long time. By the time Walpole acquired the painting and following the words of Mann, connoisseurs had declared it to be by Vasari as it is ‘much less stiff and dry’ than a Bronzino. But who is right?

Perhaps we can be guided by the great French writer, Montaigne, who was fortunate to have met Bianca while in Florence in 1580. The missing portrait is said to have reminded Walpole of the words of Montaigne, who describes Bianca in his ‘Travels’ as ‘belle à l’opinion italienne, un visage agréable et imperieux, le corsage gros, et de tetins à leur fouhait’. In short, a bosomy Italianate beauty and Walpole remarks on the parallel between Montaigne and the missing portrait of Bianca in a letter to Mann in 1774: ‘He describes her very like your-my picture’.

It is no good. I am still far from any clues as to the whereabouts of Bianca. I distract myself temporarily from my fruitless search with a surprising anecdote.

I had always known Walpole to be a prolific inventor of words. Beefy, sombre, nuance and souvenir are among some of his gifts to the English language. It was not till I happened on Walpole’s letter to Mann dated 28 January 1754, in which he describes his plans for constructing a frame for her ‘Serene Highness’ that I discovered one of his most enigmatic concoctions:

‘I must tell you a critical discovery of mine a propos in a book of Venetian arms’, Walpole ventures. ‘There are two coats of Capello… on one of them is added a fleu de luce on a blue ball, which I am persuaded was given to the family by the Grand Duke’. The Grand Duke Medici of course. Walpole rejoices in having discovered a link between the two families in a book of Venetian heraldry he just happened to be studying at the time he was arranging for Bianca’s frame to be decorated with suitable emblems. ‘This discovery indeed is almost of that kind which I call SERENDIPITY’.

There it is. The word voted the UK’s favourite in a 2000 poll (beating ‘Quidditch’ from the Harry Potter novels). The name of a song by a break out Korean pop music group, which became the first K-pop band to reach number one on the US album charts. ‘Serendipity’ is a Horace Walpole creation.

Walpole further explains in his letter to Mann that he ‘once read a silly fairy tale, called The Three Princes of Serendip’. It is the English version of a story published in Venice in 1557, which itself was a collection of oriental tales supposedly translated from Persian. Three princes find a missing camel through luck, good fortune and ‘always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of’. For instance, they notice only the grass to the left of the road where the camel travelled had been eaten. They realise the camel was blind in its right eye.

As it turns out, it is not by chance or luck at all that the three princes make these discoveries but through skill and process of deduction. Just as the successful provenance researcher is required to do.

I wonder at the memory of all the serendipitous discoveries I have made on my quest for Walpole’s missing treasures. The Sotheby’s client who brought in a Grand Tour souvenir for assessment, which turned out to be Walpole’s missing fresco. The remarkable resemblance between Walpole’s lost Turkish dagger and that of another held in the collection of Margaret, Duchess of Portland, both of which are thought to share the same provenance.

Were these truly serendipitous discoveries according to Walpole’s intended meaning of word? ‘Accidental sagacity’ or the discovery of a thing you were never looking for? Or is it precisely because I sought to look that I made these discoveries? Whatever the meaning, I am overcome with excitement at the thought that I might finally find the portrait, which inspired this extraordinary word.

It is not going to be easy. This is what we know so far:

I turn to the catalogue from the Great Sale of 1842 in search of any record of Bianca’s buyer. Sale day 20, lot 92, bought by a ‘William Seguier’, none other than the first keeper of the National Gallery. Were it that simple. Seguier was not buying for the Gallery but for one of his many wealthy clients.

I ponder Bianca’s hands. Surely I could track down a painting with such a peculiar omission? Or was Seguier canny enough to cut off the unfinished part of the painting or even commission a painter to finish them off?

Is Bianca still peering out from Walpole’s bespoke frame?

I continue my hunt. Two portraits surface to titillate me. The first lives in Italy, a portrait in Lombardy bought by the uncle of the current owner at a Christie’s sale in 1971 and said to come from the Henry Doetsch collection. Its shape has been cropped and it has undergone repainting. Remarkably, it is described as originating from Strawberry Hill and yet it is never identified as Bianca. Once thought to be Laudomia Medici, researchers have concluded she is in fact Laudomia’s relative Isabella.

I am especially doubtful of the Walpole provenance because there is no reference to Strawberry Hill in the records of the first sale where this portrait appeared. One would expect the memory of the origin of this work to have been much fresher in the minds those who handled her towards the beginning of her life, not several decades later.

The second contender for Walpole’s Bianca resides in storage at the National Gallery London. This time any and all references to Strawberry Hill have been omitted though the sitter is most certainly identified as Bianca Capello. I cannot help but ask myself whether I can take this information at face value. Is she really our Bianca or just representative of Florentine portraiture of the time?

What if I told you there was a third contender in the running? A portrait of Bianca in the collection of William Beckford, a famous collector and devotee of Walpole?

Shall we cross our hearts and hope for some serendipitous turn of events to reunite us with our tragic heroine? Or perhaps you’ve spotted the buxom beauty with the unfinished hands and grandiose frame lurking in the stately home of one of her most recent admirers?

If you have, get in touch with us to let us know via treasurehunt@strawberryhillhouse.org.uk. Good luck treasure hunters, we are counting on you to help us fill Strawberry Hill House once again with Walpole’s gems.

Credit: Fresco by Alessandro Allori representing Bianca Capello when young, Uffizi, Florence

Credit: Portrait of Bianca Capello by Scipione Pulzone 1584 Kunsthistorisches Museum

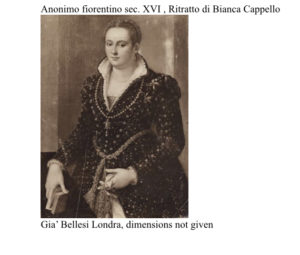

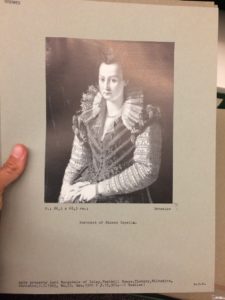

Credit: A couple of portraits strongly identified as Bianca at the Witt Library in London

Credit: A portrait of a Woman attributed to Bronzino from the Doetsch Sale in London (1895) and said to come from the Strawberry Hill Collection. In Doetsch caption is called Laudomia De Medici but recently has been identified by its owner with Isabella de Medici,Francesco’s sister.

Credit: Portrait of Bianca Capello at the National Gallery, in storage, probably 1575-85 by follower of Bronzino. This came from the John Samuel’s collection while it’s previous pedigree it is somehow unclear.

Credit: Poggio a Caiano where Bianca and Francesco were killed

Credit: A portrait of Bianca Capello was also in the collection of the eccentric William Beckford one of the greatest admirer of Walpole’s collection