Publication date: 18 December 2024

In 1752, Horace Mann, the British envoy to the Court of Florence, presented Walpole with the Portrait of the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, Bianca Capello (1548-1587). This portrait remains untraced. The iconography of Bianca Capello is much debated, and relatively few paintings are acknowledged to depict her with any certainty (Fig. 1 and 2). One of the most authoritative versions is the portrait painted by the Neapolitan artist Scipione Pulzone (1544-1598) between 1584 and 1588, now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

When Mann acquired and gifted Walpole with the portrait of Bianca Capello, he questioned its traditional attribution to the Florentine painter Agnolo Bronzino (1503-1573), suggesting, supported by local connoisseurs, Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) instead. The portrait, a half-length bust without hands (apparently unfinished), depicted an ageing Bianca. The painting reached England in 1754 and was placed by Walpole in the Round Room at Strawberry Hill, with a specially designed frame. Walpole’s letters suggest that the style was ‘less stiff and dry’ than that of Bronzino, whilst the treatment of Bianca’s features reminded him of Titian. At the great sale of 1842, the portrait was purchased by William Seguier (1772-1843), the first keeper of the National Gallery, and its trail has been lost since. Bianca seems to have been a regular presence in many English collections between the late 18th and early 19th centuries; amongst the collectors who owned her portrait were Ralph Bernal and William Beckford.

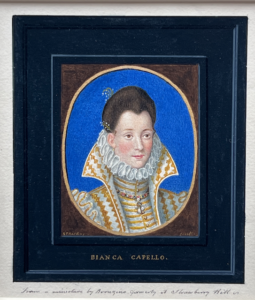

The attributions to Bronzino and Vasari are, however, unlikely for chronological reasons, whilst that to Alessandro Allori seems more probable. Walpole had at least two other portraits of Bianca Capello at Strawberry Hill: a miniature attributed to Bronzino and a watercolour (Fig. 3), also sent by Mann, which is a copy of a fabric parament realised by Jacopo Ligozzi (1547-1627).

The scandalous life of Bianca Capello, from a noble Venetian patrician family—her elopement from Venice, illicit affair with Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici, their subsequent marriage and unexpected death at the hands of Francesco’s brother, Ferdinando—has fascinated generations of writers since the 17th century, from Celio Malaspini’s Duecento novelle (Venice 1609) to French writer Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870). Henrietta Louisa Fermor, Countess of Pomfret (1698-1761), who visited Florence in the same years as Walpole, collected materials to write a short biography of the tragic heroine (The Lady’s Museum, 1760). Walpole was no exception, and it appears that the character of Bianca in The Castle of Otranto was inspired by her.

Furthermore, it was Bianca’s portrait that prompted Walpole’s invention of the famous word ‘serendipity’ (28 January 1754). Walpole commissioned a bespoke frame for the painting, embellished with the Grand Ducal coronet and the coats of arms of the Medici and Capello families. One day, whilst researching a Venetian armorial, he discovered that two versions of the Capello insignia existed, one bearing the addition of a fleur-de-lis (one of the symbols of the Medici family). Walpole, who had not expected to find an indication of the marriage between Bianca and Francesco in her family’s crest, was pleasantly surprised. In a letter to Mann, he famously described this discovery as an example of “serendipity”. The word “serendipity”, he explained, originated from the ancient Persian tale of the Three Princes of Serendip, who, during their travels, were “always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of”. The key word here is sagacity, because the three Princes, like Walpole, made their discoveries through skill and a process of deduction rather than plain luck.

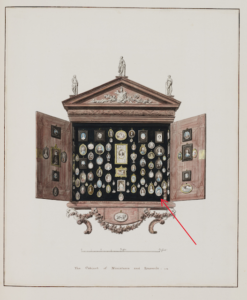

The recently rediscovered miniature was originally housed in the Cabinet designed by Walpole, which is now part of the V&A collection. At the time, it was set in an elegant enamelled frame, as clearly shown in John Carter’s drawing of the cabinet and its contents. The provenance of the miniature was discovered through a copy made by George Perfect Harding (1781-1853), a painter and copyist who visited the Walpole collection in the early nineteenth century when Anne Seymour Damer lived in the house. The copy is now in the British Museum, and it was Dr Adriana Concin-Tavella, a scholar and V&A Curator, who successfully traced the miniature’s history.

The attribution to Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614), the late Mannerist Bolognese painter, was initially suggested by the current owner Nick Cox of Periods Portraits. This attribution was later confirmed by Dr Aoife Brady, Curator of Italian and Spanish Art at The National Gallery of Ireland and a leading authority on Fontana. According to Dr Brady, the exquisitely executed portrait likely depicts a noblewoman from the Medici court, though her precise identity remains unknown.

George Perfect Harding (1780-1853), Portrait of Bianca Capello, c.1810 after an original in the collection of Sir Horace Walpole, Watercolour with bodycolour, British Museum (Museum Number 1868,1212.615).

Lavinia Fontana (1552 -1614) Portrait of a noblewoman, c. 1580-1590, oil on copper, 5.5 x 4.75cm. Collection of Nick Cox / Period Portraits.

John Carter’s drawing of the cabinet and its contents.