Unravelling the Secrets of Strawberry Hill’s Stained-Glass Graffiti

Written by Dr Rosalind White, Collections Assistant

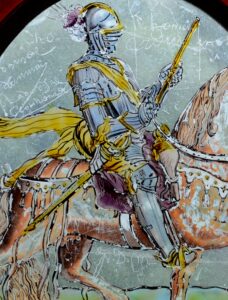

Within the Gothic splendour of Strawberry Hill’s Library, flanked by two quatrefoils bearing the white rose of York and the red rose of Lancaster, stands a magnificent traceried window. Its centrepiece, a coat of arms, is encircled by a constellation of delicate stained-glass roundels, bordered by crimson. One particular roundel captures a knight in full armour astride a caparisoned horse, poised as if in mid-motion.

Closer inspection reveals a surprising addition across the surface of the glass — a curious collection of eighteenth-century scribbles rumoured to have been etched by Horace Walpole himself. But what may have prompted him to leave these marks and what significance might they hold?

Walpole acquired his Flemish stained glass in 1750, before the library was completed in 1754; so, it’s probable that during this period, it would have been laid out for placement decisions, providing a window of opportunity for these personal musings to be inscribed.

Though these faint scribblings are largely inscrutable, some legible elements emerge: ‘Cho’ (potentially short for ‘chosen’ or ‘choice’), the initials “D. M.,” and a rectangular diagram, which some have speculated may represent a rough blueprint for the library ceiling. Most discernible is the name ‘Thomas Cromwell’ — clearly carved next to the knight’s faceplate.

Thomas Cromwell (Chief Minister to King Henry VIII during the English Reformation) was not a knight in the traditional sense; he was, however, knighted as a member of the gentry — achieving the prestigious title of Knight of the Garter in 1537. Unlike his peers Cromwell was not among the landed aristocracy; he rose to power through his skills as a lawyer, administrator, and royal advisor. Considering this context, and the seeming deliberate placement of the graffiti, I would suggest that these markings might represent a form of witty commentary on Cromwell’s unconventional path to power — drawing attention to the romanticized ideals of knighthood by contrasting them with the practical realities of political manoeuvring that Cromwell exemplified.

In Walpole’s time, the library contained both “The Life of Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex” by Arthur Collins, and “Memoirs of the Protectorate House of Cromwell” by Henry Noble, with Walpole taking great pleasure in scribbling ‘many notes on the margins’ of the latter.

Walpole was captivated by individuals who managed to secure formidable positions of power and influence. His fascination was particularly piqued by the Medici family of Florence — merchants and bankers who rose to become the city’s rulers and patrons to some of the most celebrated artists of the Renaissance. Notably, Horace Walpole’s own lineage was a confluence of political innovation and mercantile success. His mother, Catherine, was the daughter of John Shorter, a wealthy Baltic timber merchant. While his father, Robert, Britain’s first Prime Minister from 1721 to 1742, shared with Cromwell the distinction of being a ‘commoner’ honoured with the knighthood of the Order of the Garter.

For Walpole, carving the name of Thomas Cromwell beside the image of a traditional knight could have served as a subtle reflection on the broader concept of social mobility and the impact of individual achievements on historical legacy. It suggests an acknowledgment of the diverse pathways to prominence and influence—whether through the corridors of power in Tudor England, the vibrant political and cultural spheres of Renaissance Italy, or the intricate political machinations of 18th-century Britain.

Walpole had an enduring penchant for blending the realms of personal amusement with historical commentary.

His home — a Georgian construction, built to resemble a medieval gothic castle — stands today as a physical embodiment of his witty engagement with the past. He delighted in crafting elaborate backstories for his home, blending fact with fiction, and inviting his guests into a world where history was not just recounted but reimagined.

This playful attitude extended to his literary endeavours. The Castle of Otranto masterfully marries historical fiction with the supernatural; it is a narrative filled with exaggerated haunted castles and melodramatic secrets. Walpole, despite owning his own press, published Otranto anonymously, asserting on its title page that it was a translation “from the Original Italian of Onuphrio Muralto”, a 1529 manuscript supposedly “rediscovered” in the library of ‘an ancient Catholic family in the north of England’.

Walpole’s eclectic approach to collecting and curation invited those who walked the halls of Strawberry Hill into a dialogue with the past that was as much about questioning as it was about appreciating the complexity and whimsy of historical narratives. He would deliberately arrange items from contrasting epochs alongside one another — ranging from Roman sarcophagi to Renaissance busts — encouraging visitors to traverse centuries within mere steps. What’s more, many of jewels in his collection (from an ornate clock presented by Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn to shoe-buckles belonging to Mary Queen of Scots) lent history a tactile, intimate quality that stirred curiosity and encouraged imaginative engagement.

The library’s ceiling reflects this fluidity in historical representation, featuring two Knights of the Crusade adorned with anachronistic plumed helmets whom — according to familial lore — were related to the Walpoles. Our graffitied Knight in the roundel, likewise wearing plumes and full plated armour (a style that came into vogue after the 1400s, replacing the earlier chain mail) could hail from any epoch of Walpole’s choosing, from the chivalric valour of the medieval Crusades to the tumultuous dramas of the Tudor court.

Strawberry Hill’s stained-glass graffiti serves as a captivating testament to Walpole’s creative engagement with history. If you find yourself pondering these enigmatic markings or have theories of your own, please get in touch to share your thoughts, so that we can continue unravelling the secrets of Strawberry Hill together.

Sources

Serendipity #63 Dec 2021, p. 4.

The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1937-1983).

Strawberry Hill, the Renowned Seat…, 3rd ed., Sale Catalogue (London: George Robins, 1842).

“Graffiti” on the Mounted Knight roundel in the library window. Image credit: Miriam Kleingeltink.

Walpole identified himself as ‘very Medicean’ (Letters vol. 15: p. 278) and acquired numerous artifacts associated with the Medici family, including this painting of Catherine de’ Medici and her children, which returned to the Gallery at Strawberry Hill House in 2021. Image Credit: Matt Chung.

Clock, presented by Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn on the morning of their marriage in 1532. It is believed to have been given to Horace Walpole by Lady Germain and was kept in the Library at Strawberry Hill between 1747 and 1795. The clock returned to Strawberry Hill in 2018 as part of the Lost Treasures Exhibition. Image credit: Kilian O’Sullivan.

The Library Ceiling. Image Credit: Matt Chung, 2010. The ceiling depicts two knights echoing the knights on horseback in the window glass. It celebrates the family past and was sketched by Walpole, drawn in detail by Richard Bentley, and painted by Andien de Clermont. Note the plumed helmets anachronistic to the Crusades and the Saracen’s head from the Walpole family crest, symbolising their participation in the Crusades to the Holy Land.