Horace Mann, British Envoy to Florence, was a close correspondent and generous benefactor to Horace Walpole, providing numerous artifacts for Strawberry Hill. In May 1767, Mann sent Walpole a small ancient bronze bust of the Roman emperor Caligula, reportedly one of the first treasures unearthed from Herculaneum.

Walpole was ecstatic. The bust, a high-quality artwork, depicted one of Rome’s most notorious villains. Initially a noble ruler, Caligula became increasingly self-indulgent and cruel, traits that fascinated Walpole. He expressed his satisfaction to Mann:

“I gaze on it from morning to night. It is more a portrait than any picture I ever saw. The hair and ears seem neglected, to heighten the expression of the eyes, which are absolutely divine, and have a wild melancholy in them, that one forebodes might ripen to madness.” (Walpole Correspondence, 30 May 1767)

At the 1842 Strawberry Hill sale, the bust was purchased by collector William Beckford, and its traces were subsequently lost.

Fortunately, Walpole’s collection is one of the most thoroughly documented 18th-century collections. This is thanks in part to the detailed drawings of rooms and objects commissioned by Horace from the draughtsman John Carter, including a life-size drawing of Caligula (Fig 1).

Generations of enthusiasts searched for the small Caligula using Carter’s drawing until its recent serendipitous discovery in the Schroder family collection. Acquired in the late nineteenth century by Baron Sir John Henry Schroder, the connection to Strawberry Hill was forgotten. The bust was described in the Schroder collection catalogues as a possible Renaissance bronze of a youth.

The discovery of the lost bust of Caligula in the Schroder collection was confirmed by comparing the small bronze with John Carter’s drawing. This find raised significant questions:

Is it an ancient statue or a Renaissance bronze?

Initially, the lack of patina suggested a sixteenth-century origin. However, the inlaid silver eyes and recent metallurgical analyses confirm that the bronze’s composition aligns with ancient dating.

Is it truly a bust of Caligula?

The final validation came from German archaeologist Dietrich Boschung, the foremost expert in Caligula’s iconography. His identification is further supported when comparing the bust with other contemporary portraits.

Walpole’s busts small scale suggests it may have served a ritual function, displayed in public or household shrines and altars. Until now, only seven small-scale bronze portraits of the emperor were known. (Fig 2)

A bronze from Herculaneum?

Historical records, likely provided to Horace Mann at the time of acquisition, describe how Emmanuel Maurice de Lorraine, Prince d’Elboeuf (1677-1763), discovered the small bronze bust at Herculaneum during his excavations starting in 1709.

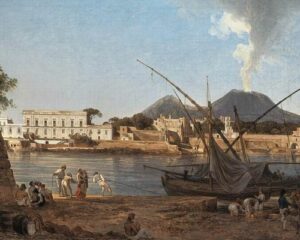

A Prince of Lorraine and descendant of the House of Guise, arrived in Naples in 1707 as cavalry commander, residing in one of its richest palaces and owning another in Portici, where he transformed an old hospice into a Villa of Delights (Fig. 3). During the expansion of the villa’s hydraulic system on the site of ancient Herculaneum, the first discoveries were made.

Some sculptures excavated by Elboeuf were used to decorate his villa, while others were exported. To date, the only statues known to have come from his excavations are the three famous “Herculaneum women”, which were gifted by him to Prince Eugene of Savoy and are now in Dresden (Fig. 4).

The Bronze portrait bust of Caligula can now be added to the ancient statues from Herculaneum once in Elboeuf’s collection.

The discovery of the Caligula bust occurred in a serendipitous manner, fittingly so as Horace Walpole himself coined the term ‘serendipity.’ It means making happy and unexpected discoveries by accident, though Walpole emphasized the importance of sagacity, or perceptiveness, in recognizing their significance.

For years, curator Silvia has meticulously researched the Walpole collection, familiarizing herself with John Carter’s drawings and tracing numerous objects and paintings. Her extensive provenance research and collaborations with various institutions have been instrumental in identifying many lost pieces, including items in the Schroder family collection.

During one such collaboration, while examining the Schroder collection, Silvia “accidentally” discovered the small bust of Caligula. This find was only possible because of her deep knowledge and expertise, demonstrating the true essence of serendipity—unexpected discoveries recognized through keen observation.

Fig. 1 John Carter, Bust of emperor Gaius (Caligula) in the Horace Walpole Collection, date, medium, size, Sketch Book, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California [RB 130368]

Fig. 2. Left: Bronze portrait bust of the emperor Gaius (Caligula), Roman, ca. 37-41 CE, H 25 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (no. 23.160.23). Right: Bronze portrait head of the emperor Gaius (Caligula), ca. 37–41 CE, H 6.8 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (no. 25.78.35)

Fig. 3 Joseff Rebell (1787-1828) The Mole at Portici, with Villa Elboeuf in the background on the left side of the painting, 1818. Neue Pinakothek, Munich.

Fig. 4 Small and Large Herculaneum women, Roman, 30–1 BCE. and 40–60 CE, marble, Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden