Strawberry Hill House is internationally famous as Britain’s finest example of Georgian Gothic Revival architecture.

Finding the Lost Portrait of Baron of Sheffield

Posted on 03 September, 2018

In this eight instalment of the hunt for the Lost Treasures of Strawberry Hill, a treasure is found. Art historian and super sleuth, Silvia Davoli, reveals how she tracked down a lost portrait of the Baron of Sheffield only to discover a mystery within the mystery of its disappearance from Walpole’s gothic villa.

When I first enter, I think to myself that it is an office much like any other that one might expect to find in bustling central London. I take in the sleek furnishings and hear the faint whir of the computers. Then I see him, the unmistakeable painted face of the Baron gazing out from the frame on the wall and a frisson of excitement overcomes me. I have found Walpole’s lost portrait of the nobleman, John Sheffield. Another treasure is restored.

Oil on panel and 31 by 23.5 inches, the portrait of the 2nd Baron of Sheffield once hung in Walpole’s glorious Gallery at Strawberry Hill, alongside the basalt bust of Emperor Vespasian and the portrait of a young man in fur, said to be by Giorgione. There he is, peering out from the view of the gallery realised by Edward Edwards in the 1780s. Son of Edmund, 1st Baron of Sheffield (1521-1549), and Lady Anne de Vere, daughter of the 15th Earl of Oxford, John Sheffield is thought to have been born sometime after his parents married before 1538.

John inherited by 1552, two years after his father’s death, and married Douglas Howard (1542-43 – 1608), the eldest of the three daughters of the 1st Baron Howard of Effingham, in 1560. I found his portrait in the Strawberry Hill Great Sale Catalogue of 1842, where it is described as: ‘Portrait of John Sheffield husband of Lady Douglas Sheffield on whose account it was surmised that he was poisoned by R[obert] Earl of Leicester by Sir Antonio More’.

Of course this is not the only painting said to be by Antonis Mor, which Walpole housed in the Great Gallery. My hunt for the lost treasures led me on the trail of a portrait of Marguerite de Valois, Duchess of Savoy, also attributed to Mor by Walpole. As I prepared to trawl through the records for any sign of the Baron, I wondered whether he would return to me as easily as Marguerite, whom I discovered buried in the pages of the catalogue raisonné of Willem Key during one of my research trips to the Warburg Institute.

Just as I had done while searching for Giorgione’s young man in fur, I consulted the Gentleman Magazine’s detailed review of the 1842 Great Sale. I learned that the painting of the Baron is inscribed with ‘Anno 1552 aetatis 31’. He was painted in 1552 at the age of 31.

How did the 31yr-old nobleman of Butterwick, Lincolnshire come to reside in Walpole’s glittering Gallery? The clue came in the form of a letter to Lord Hardwicke, which Walpole penned on 29 January 1777. I am astonished to discover that the portrait featured on a long shopping list of artworks, which Walpole purchased from Buckingham House on 25 February 1763 when Sir Charles Sheffield sold it to King George III.

Together with the Baron, Walpole took home a number of drawings after the now lost originals by Holbein and Lucas Vorsterman among others. I marvelled at Walpole’s foresight in gathering together such invaluable pieces. Could I possibly hope to return all of them to his former home? My resolve hardened as I returned to the Great Sale catalogue to search for more crumbs left by Mor’s Baron.

I pored over the entry for Day XXI, lot 63. The painting was bought by a ‘Richard R. Preston Esq.’ at the Strawberry Hill sale for £14.14.0. Richard Rushton Preston of Preston Patrick in Kendale (1811-1845). Thirsting for a more detailed history of this man I make a visit to the National Archives at Kew where I locate his Will dating from 1848. It seems Richard was quite fond of the Baron. He kept the painting to the very end, only after which it passed through several sales during the 20th century including:

I arrived at a roadblock. Where had our Baron gone to after the 1937 sale? Did he remain with the buyer who attended Leggatt Brothers that April or had he since changed hands again? I had been hurtling along a high-speed chase, leaping seamlessly from one clue to another and all of a sudden I began to tread water. I wondered if I might find anything in the Heinz Archive at the National Portrait Gallery to put me firmly back on track. The records held there had been so instrumental to my discovery of the two versions of the missing Falkland portrait so I hightailed it back to Orange Street.

My instinct proved correct. A sale catalogue entry helped propel my search right into the 21st century:

Had the Baron truly gone full circle and returned to his ancestral home after so many years? I was buoyed by the discovery and began to devise a means of contacting the present-day Sheffield family. I could scarcely believe my luck when the heir to the Sheffields invited me to his London office to inspect the painting. All along the lost treasure had been sitting on his wall.

The mystery was solved, another lost work unearthed and ready to return home to Strawberry Hill to reunite with the other masterpieces from Walpole’s extraordinary collection in a once-in-a-lifetime exhibition. Despite my initial struggle to lift the shroud of mystery it all felt somewhat simple. Even serendipitous. That was until I uncovered the mystery within the mystery of the lost Baron, and began to ask myself whether he was in fact the Baron I had been searching for after all.

If my calculations are correct, and John Sheffield was born after 1538 (the year his parents married) and before 1543 (one year before his father made his Will) then by 1552, the year with which the portrait is inscribed, the Baron could only have been as old as 14. Yet, if the inscription on the canvas is authentic, and I truly believe it is, the sitter in the painting was born in 1521.

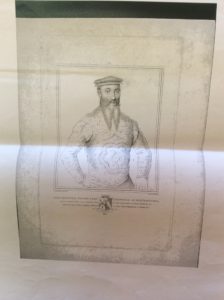

In the Heinz Archive, I found a 19th century print by Robert Graves (1798-1873) of our painting with an inscription, which confuses matters even further:

‘John Sheffield Second Lord Sheffield, Anthony More… ob. 1568 aetatis 37’.

If John was said to be aged 37 in 1568, this would mean he was born in 1531. Consequently, when our portrait was painted in 1552, he would have been 21yrs old, not 31 as the inscription would suggest.

We might have found Walpole’s missing painting, but can we be sure it is of the sitter we thought we knew? Walpole himself believed it was the Baron, as can be seen from the label on the verso of the painting, which though tiny and difficult to read looks very much like Walpole’s handwriting:

‘John 1st lord Sheffield

Husband of Lady Douglas Howard

<?> by some <?> as the wife of Robert Dudley Earl of Leicester <??> she was mother of Robert Dudley. <?> Duke of Northumberland.

…

By Antonis Mor’

But the dates do not appear to be consistent with John Sheffield’s own timeline nor Antonis Mor, who is said to have visited London on only two occasions. According to Max J. Friedlander, his first visit was in 1554 to paint Mary Tudor and his second in 1568.

Just when I thought my archival research on this painting had ended with its discovery, it has inspired a whole host of new questions about the identity of the portrait’s sitter and its attribution. Can you help me to make head or tail of it? You can make a first-hand inspection of the Baron yourself in October when he returns to Strawberry Hill House.

It is just a few short months away. Do not forget to book your ticket here.

Portrait of John, 2nd Baron Sheffield Attributed to Antonis Mor (1516/20– 1575/6), 1552. Oil on board, 96 x 77 cm. Private collection.

Verso of the painting, with handwritten labels.

Robert Grave’s Portrait print of John Sheffield (Heinz Archive).