Strawberry Hill House is internationally famous as Britain’s finest example of Georgian Gothic Revival architecture.

From Strawberry Hill to the Hamilton Sale 1882

Posted on 31 July, 2018

In this seventh instalment of our special blog series, we continue to follow art historian and provenance researcher, Silvia Davoli, as she goes on the hunt for the lost treasures of Strawberry Hill House. Silvia follows the trail of three sculptures that embody Walpole’s fascination with the antique world and formed a core part of his iconic collection.

There it sits, unassumingly, at the back of a crowded collector’s cabinet. The lustrous bronze is barely perceptible beneath a greenish layer of patina. The tarnished silver eyes can scarcely reflect the modern halogen lighting that illuminates the collector’s living room, many miles and hundreds of years from the Tribune at Strawberry Hill House where it once resided.

My imagination has led me to believe this is where we might now find the bronze Caligula head that starred in one of Walpole’s glass cabinets in the Tribune at Strawberry Hill House. I wait impatiently for this fictionalised collector to discover my search for the lost treasures and write me in order to reunite Caligula with his former bijou home. Dear collector, are you reading this now?

As we have already discovered together, the bronze Caligula head is just one example of many artefacts exhumed from the ancient world or created in homage to it, which were collected avidly by Walpole. As a young Grand Tourist, Walpole’s voracious appetite for the antique inspired him to collect objects that shed light on the everyday habits and styles of the ancient Romans, including coins, medals, vases and of course sculptures.

I am transfixed by three such sculptures. All were once housed in Walpole’s gothic villa, all are unseen since the Great Sale of 1842, when they were purchased by dealer Robert Hume on behalf of William Beckford, the famous collector and creator of Fonthill Abbey. Later, Beckford’s objects were to pass into the collections of the Duke of Hamilton. Where to begin in unearthing these precious needles in the haystack of the world’s private and public art collections?

Fortunately, we are not without investigative tools. I have uncovered three ornate illustrations of these objects and I am hopeful that this visual evidence will suffice to bring us closer to tracking down the missing objects.

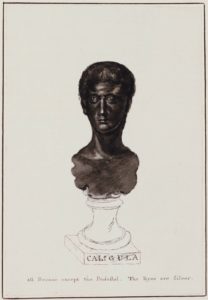

Caligula

Let us begin with the ghostly head of Caligula, the small bronze bust with ethereal silver eyes. When I consult Walpole’s ‘Description of the Villa’ from 1774 I learn that the bust was excavated for the Prince d’Elbeuf (1677-1763) from the ancient Roman town of Herculaneum, which was devastated by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. A French peer and archaeologist, the Prince sponsored the first digs on the site of the old theatre at Herculaneum at the beginning of the 18th century when the ruined town was first rediscovered.

Prince d’Elbeuf sold Caligula to Horace Mann who in turn gave it to Walpole. ‘This exquisite piece is one of the finest things in the collection’, enthuses Walpole in his ‘Description’, ‘and shows the great art of the ancients’. Eager for a clearer visual, I turn to the fine drawing of the bust executed in the 1780s by the English draughtsman and antiquary, John Carter, commissioned by Walpole to document the changing appearance of Strawberry Hill and its tremendous collection.

I study Carter’s gleaming rendition of Caligula’s high forehead, small thin-lipped mouth and prominent chin and the unmistakeable glint of those silver eyes. I wonder at Walpole’s suggestion that the portrait bust depicts the emperor ‘at the beginning of his madness’. From the drawing, I deduce the size of the head is approximately 14cm (5.5 inches).

Could this measurement possibly link us to another breadcrumb from the trail left by the tiny bronze emperor after it departed Walpole’s collection in 1842?

At first glance, Caligula does not seem to appear in the catalogue for the Hamilton Palace Sale in 1882. I take another, closer look and find the description for lot 470: ‘A small antique bronze bust of Alexander the Great on marble socle 4 1/2 inches. From Strawberry Hill (bought by W. Boore £21)’. Is this our lost bust? Maybe Mr Boore is the missing link in our chain of provenance. Active between 1865-1886, William M. Boore was based at 54 the Strand, London. He sold works of art to the British Museum and to the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford.

Of course, when you begin your own search, do not forget that our Caligula will almost certainly have developed a patina over time and the eyes may have tarnished and may no longer be visible. Yet, this small bust with its depth of character is integral to the Strawberry Hill collection and must be traced. Perhaps it is displayed on a museum shelf, or it is hiding in the back of our collector’s cabinet. Perhaps it even sits on a bedside table, besides a stack of novels and a box of tissues, a cherished, special possession. Can you help me find it?

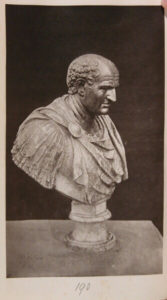

Vespasian

Unlike the Caligula, the second bust for which we are searching might appear now just as it looked when housed in the gilded Gallery of Strawberry Hill. Displayed by Walpole in the bay to the right of the chimney piece, the imposing basalt figure of Emperor Vespasian is listed in the 1842 Great Sale catalogue as lot 73: ‘a magnificent colossal bust… a most splendid specimen of sculpture, the countenance powerfully expressive of the character of this monarch’.

Crafted from basalt with agate marble drapery, the bust is not ancient, as Walpole believed it to be, but an artful 16th century imitation of antique statuary. Nonetheless, it was positioned by Walpole on a green marble plinth, atop a genuine Roman sepulchral altar. A bas-relief on the altar depicts a man sacrificing with the inscription:

‘T.I. CLAVDIVS AVG.L

DOLCILIS

AEDITVS AEDIS

FORTUNAE TVLLIANE’

Carter’s illustration of the six feet high Vespasian bust and pedestal situates him exactly as the 1842 sale catalogue describes. The dark, igneous basalt of the Emperor’s head looms out at us from Carter’s rendition of the delicate trefoil panelling of the Gallery walls. With such a prominent position in Strawberry Hill House, it is clear to me Vespasian was beloved as one of Walpole’s star objects. How overjoyed the great man of letters would be to learn the statue might one day return to us to cast his stern imperial gaze down the Gallery.

Our hope rests on the last remaining trace of the bust, which features in the Hamilton Palace sale catalogue from 1882 as lot 190. Sold by Christie Manson & Woods Ltd. in one of the five top sales said to have established the auction house’s global status, it was bought by dealers T. Agnew & Sons. It appeared once more on the art market in 1893 at the June Christie’s sale of the collection of the Right Hon. Revelstoke, when it was purchased by antique dealer Charles Davis. Davis sold works of art to prominent collectors of his time including the Rothschilds and Richard Wallace. He also had connections with Russian collectors.

Since Davis, the trail has gone cold but we can be sure that such a distinctive piece is most probably now sitting in a prestigious collection, perhaps even in Russia. But whose collection? Probably a grand one!

Jupiter Serapis

As I conjure up visions of grand entrance halls and dusty sitting rooms, I wonder if perhaps a similar fate befell the basalt head of Jupiter Serapis. Bought by Sir William Hamilton from the Barberini collection in Rome, it was sold to the Duchess of Portland. Upon her death, Walpole scooped it up and placed it firstly in the Round Drawing Room at Strawberry Hill and then later in the Indian blue damask Beauclerc Cabinet.

I leaf though the pages of Walpole’s ‘Description’ until I reach his entry on the Cabinet’s contents. ‘The head of Jupiter Serapis, in basalts. The divine majesty and beauty of this precious fragment prove the great ideas and consummate taste of the ancient sculptors’, Walpole poeticizes. He is scant with his physical description and so I trawl for an illustration by Carter to help me envisage the lost treasure.

Carter’s careful hand depicts the Graeco-Egyptian deity as a dashing, Greek god with a chiseled nose and almond-shaped eyes peering out from beneath a halo of tightly curled hair. He is crowned with a gilded corn measure or modius, which was added by the sculptures Ann Damer, one of Walpole’s protégées, in 1787. Damer also repaired some of Serapis’ curls with wax.

Last seen at the 1882 Hamilton Palace collection sale, when it was purchase by renowned Italian antique dealer jeweler and collector, Allesandro Castellani for £106-1s, the bust’s whereabouts remain a mystery. I think to myself that it should be simple enough for us to track down Serapis with the detailed illustration provided by Carter and yet two details confound me:

It seems that during the 18th and 19th century, it was rather common to confound materials but obviously this makes my research more difficult. Was it bronze or basalt? Might it simply be a cataloguing error? What if we are on the trail of a different bust with no connection whatsoever to Walpole?

Your help is needed more urgently than ever to gather together the scattered pieces of Walpole’s extraordinary collection of antiques. With the last known traces of these statuettes recorded in the 19th century, we are going to need to redouble our efforts to hunt them down into the present day.

Remember to keep in mind the following:

These pieces were so integral to Walpole’s collection and encapsulated his zeal for the ancient world so completely. To bring us closer to restoring Strawberry Hill so that it is not simply the house that it once was but also the home of the esteemed collector and antiquarian, it is especially important that we recover the statuettes. If you have not yet joined our treasure hunt, now is the time to begin.

Happy hunting and don’t forget to get in touch with your findings via treasurehunt@strawberryhillhouse.org.uk. Let’s bring Walpole’s collection back to life.

Bust of Emperor Vespasian, a photograph of the bust which illustrates the Hamilton Palace sale catalogue (1882)

John Carter, Caligula’s bust, courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

Detail of the bust in the Gallery at Strawberry Hill

Detail of the altar

John Carter, Jupiter Serapis, courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University