The mystery of the painting that inspired ‘The Castle of Otranto’

29th March 2018

When we last left Silvia, she was on the hunt for the lost dagger of King Henry VIII. We rejoin her now in her quest to find another lost treasure of Strawberry Hill House: a painted portrait which inspired a gothic ghost story.

There is something truly magical about the work of a provenance researcher. Some extraordinary alchemy is involved in conjuring up all the hidden stories interwoven in an object’s past and in unveiling its secret history. I thought I had drawn on all my wizardry skills in the hunt for Horace Walpole’s lost Turkish dagger. As I have just discovered, there exists an object of even greater curiosity still missing from Walpole’s collection that has pushed my powers of investigation to their limits.

It is a painting attributed to Paul Van Somers of Henry Carey Lord Falkland (1575-1633) and was described by Walpole as once hanging on the window side of the great Gallery at Strawberry Hill. I am astonished to discover that it was the very painting that inspired the scene in Walpole’s gothic novel, ‘The Castle of Otranto’, in which a portrait comes to life. Manfred, lord of the castle, has just declared his intentions to divorce his wife and offers himself to his daughter-in-law when he witnesses the painting of his grandfather ‘quit its panel, and descend on the floor with a grave and melancholy air’.

Leafing through my research on gothic literature, I soon learn that the idea of a figure stepping out from a painting had important consequences in the gothic literary canon. It provides the origin of the idea, conveyed in both visual and liberal arts by proponents such as Mary Shelley, that what is lifeless can suddenly live. I also discover the this eventually evolved into the notion, exemplified most notably by Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray, that art can become life and vice versa.

But exactly what was the painting that inspired this iconic literary moment and where did it disappear to?

For a very long time I believed that Falkland’s portrait, once displayed in the great crimson and gold Gallery at Strawberry Hill, came to reside in the collection of the Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation in Houston, Texas. Yet, even the most accomplished researchers must continuously question their beliefs and recalibrate their findings in light of new discoveries. Setting out to retrace the provenance of the portrait backwards from Houston to Strawberry Hill, I was to make my biggest discovery yet.

Armed with a handful of sources, I began to map out the trajectory of the painting’s journey from Walpole’s grand Gallery to the USA. I began my search in Walpole’s detail-rich ‘Description of the Villa’. He tells me that the painting is of ‘Henry Carey Lord Falkland, deputy of Ireland, and father of the famous Lucius lord Falkland; in white by Van Somers’. Unfortunately, this is about as much detail as Walpole is willing to divulge.

In the many printed tomes of Walpole’s correspondence he remains tantalisingly tightlipped about the painting’s provenance. Where it came from, when and from whom – sadly, he has withheld all of these details. I am not discouraged. There are more magic research tricks up my sleeve that I have yet to perform.

At the very least, I know that Falkland’s portrait was with Walpole at Strawberry Hill by 1762. The catalogue of the Great Sale of 1842 also records the painting was sold as lot 99 to a John Tollemache Esq. of Helmingham Hall. An engraving of the portrait executed by George Perfect Harding also draws the connection between Walpole and Helminghall Hall: ‘Henry Cary Viscount Falkland From the original by Vansomers at Strawberry Hill now in the Collection of John Tollemache Esq. MP’ it reads.

It seems that Tollemache was so proud of the painting he was not content to let it hang on the wall of his Suffolk estate but wished to share it with the public. I uncover a copy of a catalogue of the 1857 Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition, which records Lord Falkland’s portrait, ‘in the coll[ection] of Tollemache John MP’, as piece number 41 of the works displayed in the British Portrait Gallery. Obviously if I were to have any chance of illuminating the portrait’s shadowy past, I would have to conduct a close study of the Helmingham Hall dossier and a file corresponding to Falkland’s portraits at the Heinz Archive and Library at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

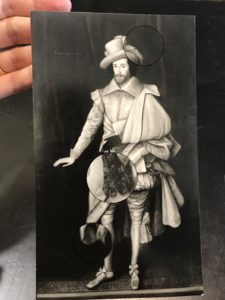

The Heinz Archive is a fantastic resource for my research and boasts the most helpful and supportive librarians. Determined to flesh out the details of the portrait’s movements I race through the Orange Street entrance, report to Reception and quickly pull up a chair in the Collected Archives room to set about poring over the yellowing records. I take my time studying several images of the portrait. Lord Falkland in black and white. Lord Falkland in colour. White robes flowing behind him, the painting really does appear to suggest that he might at any moment walk out from his frame.

Yet despite my best efforts at scouring the archives there is absolutely no mention of the Falkland portrait in the 1958-59 inventory of paintings in the Helmingham Hall collection.

I pause and consider this. Of course, it stands to reason if the painting were no longer in Tollemache’s collection at the time Sir Ellis Waterhouse completed the Helmingham Hall inventory. This is exactly what Sir Waterhouse himself helpfully confirms in a handwritten record I uncovered earlier in the Lewis Walpole Library. In the record, Waterhouse informs Wilmarth S. Lewis, perhaps the most famous researcher on Horace Walpole, about the sale of the Falkland portrait in 1953 at which point it leaves Helmingham Hall.

But where did it leave for? Could the Tollemache sale provide the missing link between Walpole and the portrait in Houston?

Sensing I had yet to exhaust the research potential of the Heinz Archive, I continue trawling and unearth a surprising letter. Dated 12 March 1985 it is addressed from a Charles Jerdein, presumably an antiques dealer, to the then Director of the National Portrait Gallery in London. Jerdein offers the following portrait for sale: ‘Viscount Falkland by Van Somers (1576-1621) oil on canvas, 216,5 cm x 127 cm Dated 1603… Provenance: Lord Falkland by descent’.

Where is the mention of Walpole? Of Strawberry Hill? Or of the 1842 sale?

Puzzled, I decide to pen a letter to the current Lord Falkland. He graciously responds to confirm that the portrait had been held by his family for centuries up until its sale to the collection in Houston. With Lord Falkland’s invaluable insights, I decide to look afresh at the images of the portrait held in the Heinz archive. As I make a much closer inspection of the images, I realise I have made a stunning discovery. There are in fact two versions of the Falkland portrait.

I only had to compare a colour image of the portrait with another black and white image of what I assumed was the same painting to notice three differences. See if you can spot them too:

One painting in Houston, one still afoot and most likely a copy of the original commissioned by Walpole. A lost treasure of Strawberry Hill after all. Instead of retracing the portrait’s provenance backwards from Houston, I understand I need to pick up the thread from Tollemache and continue my hunt in a new and unknown direction.

Once again, the treasure trove of the Heinz Archive delivers up an enticing nugget of information and a possible stepping stone to help me along my way. I find an entry from a 1970 Leggatt Brothers sale catalogue which reads as follows:

‘SOT LONDON 15/7/1970 lot 52:

English School, 1603

A portrait of Henry Carey, first Viscount Falkland…

Provenance:

Waldegrave’s, Strawberry Hill Sale, 1842 lot 99 as Vansomers; Tollemache, Helmingham Hall’

Waldegrave, Strawberry Hill, Vansomers, Tollemache. All the identifying flags I needed to spot in order to be able to bridge the gap between Walpole and the missing portrait’s current owner. But who was it sold to at the 1970 London sale? Where does the bridge come to an end? Brimming with hope, I grasp for more clues. Just one surfaces from an annotated copy of the Leggatt Brothers catalogue owned by the famous dealers themselves:

“£400 – Thorburn”;

“bi”.

Could Thorburn be the keeper of the lost treasure? “Bi” would appear to indicate the painting was bought in rather than sold but can we be sure Thorburn is its last and perhaps current owner? And who on earth could he or she be?

Two portraits. One in Texas. One still at large, although most probably in the United Kingdom. The mystery remains but you might very well be the one to help me solve it. Here are a few pointers to guide you in our quest:

Happy treasure hunting and don’t forget to get in touch with your findings via treasurehunt@strawberryhillhouse.org.uk. With your sleuthing, we might yet see Lord Falkland’s portrait hanging once again from the wall of the great Gallery at Strawberry Hill.

Credit: Marcus Geeraerts (1561-1635), Portrait of Henry Carey, Lord Falkland, Deputy of Ireland, (c.1575-1633), c.1762, oil on canvas, 215 x 127 cm, Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation, Houston, Texas (BF/1985.19).

Credit: Paul van Somer, Elizabeth Cary, Viscountess Falkland (1585-1639), oil on canvas, 219.7 x 129 cm, Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation, Houston, Texas, BF.1985.2.

Credit: Joseph Constantine Stadler, The Gallery at Strawberry Hill, no date, aquatint on paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Credit: Lord Falkland, images sourced at the Heinz Archive by curator Silvia Davoli.

Credit: Lord Falkland, images sourced at the Heinz Archive by curator Silvia Davoli.